Aviation Digest LAMSON 719 Part 3

This article is Part 3 from a three part series that was written by our own Rattler 20, Captain Jim E. Fulbrook, Ph.D., MSG and published in the United States Army Aviation Digest in June, July and August of 1986.

Webmaster note: This article refers to the operation as “LAMSON 719”. The correct name of the operation is actually LAM SON 719, referring to the birthplace of a Vietnamese hero who led an army to expel the Chinese from Vietnam in the 15th Century. The use of “719“ signifies the year “1971“ and the battle area along Route 9. Also noteworthy is the fact that the scan of the articles was less than optimal, several of the images in the article were unusable. You can see the original scanned documents here.

Reflections and Values

The June 1986 issue of the Aviation Digest contained “Part 1: Prelude to Air Assault“ of this three-part series. It reviews the history of the Vietnam War leading up to LAMSON 719, the most significant airmobile/air assault battle of the war and the only historical example of contemporary Army Aviation operating in a mid-intensity conflict. Part 1 defines the levels of conflict, describes Army Aviation missions and units, and discusses the concepts of fire support bases and airmobitity in the Republic of Vietnam. it also discusses the Vietnamese culture and its impact on military operations.

Last month’s “Part 2: The Battle“ describes immediate events leading up to LAMSON 719–the operations order, the battle itself and some of the battle statistics.

This article concludes the series by reviewing battle statistics and official operational and afteraction reports of the 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile) (April to May1971). These reports and several other units” and commanders” debriefing reports on LAMSON 719 were deciassified after 12 years (DOD Dir. 5200.10) and are available through the Defense Technical Information Center.

Also, this article presents comparison statistics on the Vietnam War to put the LAMSON 719 battle in better perspective; finally, the author gives some personal reflections about his experiences in Vietnam and Laos during LAMSON 719.

The value in studying the Vietnam War, and in tapping the “corporate memories” and experiences of those soldiers who served in Vietnam, cannot be overemphasized.

This article stands alone for most of its information content. That is why a summary of the LAMSON 719 battle is provided. But, readers can get more information and definitions of terms by reading Parts 1 and 2. (Copies can be obtained by writing to Aviation Digest, P.O. Box 699, Ft. Rucker, AL 36362-5000, or by calling AUTOVON 558-3178.)

Various official reports written in 1971 about LAMSON 719 total more than 300 pages. Space does not permit a complete review here, but the prophetic nature of the recommendations proffered by the chain of command in its review of the battle and the lessons learned are truly remarkable. Indeed, Army Aviation has refined and evolved its tactical doctrine beyond Vietnam, but it has not “reinvented the wheel.” Army Aviation Operations and lessons learned during LAMSON 719 probably contribute to current and developing evolution of Army Aviation tactical doctrine more than any other operation has in the past 20 years.

LAMSON 719 Summary

The principal objectives of LAMSON 719 were to interdict and disrupt the flow of enemy troops and supplies into South Vietnam along the Ho Chi Minh Trail1n Laos. LAMSON 719 became the most serious test of the concept of airmobility. It came in a setting of helicopters operating on the battlefield as a critical member of a combined arms team, on a combined operation, in a deep attack.

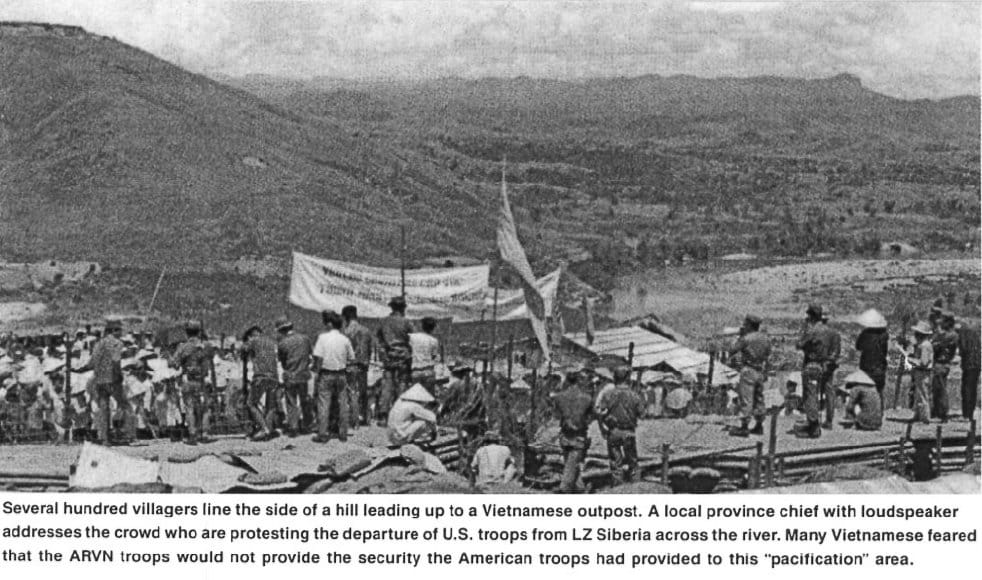

LAMSON 719 was the first major test of the formalized Vietnamization effort. It bought more time for the Vietnamization program and more safety for the continued withdrawal of U.S. troops, by damaging North Vietnam’s ability to launch offensives. And, hopefully it helped alter North Vietnam’s intransigence in peace negotiations, which then were underway.

LAMSON 719 was launched across the Vietnam–Laos border in the vicinity west of Khe Sanh on 8 February 1971. The operation lasted 45 days and was terminated, for the most part, on 24 March 1971. It involved about 17,000 Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) troops supported by U.S. Army units of the 24th Corps. All aviation Operations were principally supported by the lOlst Airborne Division (Airmobile). Some 10,000 U.S. troops supported the ARVN attack into Laos.

In LAMSON 719, the United States committed more air and artillery support to a single battle than at any other time during the Vietnam War. Aviation assets in the lOlst were beefed up to the then equivalent of a three—division size force for an area of operation in Laos of about 53 km x 20 km. The lOlst afteraction report listed assets of 659 helicopters in support of the operation. The ARVN deep battle was conducted without any U.S. ground forces or advisors entering Laos; but, U.S. air support was used to its maximum for transporration and firepower. The ARVN forces would become wholly dependent on U.S. helicopter support for resupply and troop insertions and extractions in Laos.

Strength of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) was estimated to be 30,000 combat and 20,000 logistics troops in two main staging areas in Laos. The NVA expected an attack into Laos and upgraded its defenses and troop strength purposefully, to stand and fight. The enemy had several hundred antiaircraft weapons circulated among several thousand prepared emplacements, and artillery and armored regiments ready to respond to the attack.

The operations order for LAMSON 719 was written and generally executed in four phases:

- Phase I started 1 February 1971 and consisted of U.S. units reopening the Khe Sanh base and airstrip, and clearing Route 9 (a 1- and sometimes 2-lane dirt road) from Fire Support Base (FSB) Vandergrift to the Laotian border. Route 9 started in South Vietnam on the coast in Quang Tri and coursed westward across Vietnam and Laos. In 1968 Khe San was the site of a major battle with U.S. Special Forces and Marine units battling NVA units. The Khe Sanh plateau had been abandoned for more than 2 years before LAMSON 719 was launched.

- Phase II began on 8 February 1971 and consisted of ARVN units attacking westward into Laos along three lines. Armor units spearheaded an advance down Route 9, while infantry units were helicopter assaulted to advance along the southern flank in the panhandle of Laos, and on a well–defined terrain feature called the “escarpment.” Airborne and ranger units were helicopter assaulted to set up FSBs and flank protection to the north of the armor attack. Phase 11 continued with coordinated attacks to the west as far as a town called Tchepone, some 26 miles into Laos. By 10 March Phase II was completed.

- Phase III was exploitation. Search and destroy Operations were conducted against enemy forces and bases. These operations were ongoing throughout Phase II.

- Phase IV consisted of the withdrawal of ARVN troops from Laos. This phase lasted from 11 to 24 March.

Throughout the operation, enemy opposititm was intense. There were more NVA troops than was originally thought, and they had a great deal more armor (especially tanks) and artillery than expected. ARVN troops were subjected to infantry and tank assaults and bombardments by rockets, artillery and mortars. Several embattled ARVN bases were overrun or abandoned in the face of intense NVA attacks.

Despite massive U.S. air support and firepower, the LAMSON 719 battle continued into March. Personnel and materiel losses mounted steadily against the ARVN and the NVA gained the upper hand. Indecision and troop discipline slowed ARVN movement, especially in armor units, and reserves were not committed when the battle momentum turned againSt the outnumbered, outgunned ARVN troops. It was during LAMSON 719 that the first head-to-head armor battles took place in the Vietnam War which, incidentally, were won by the ARVN units.

One of the most serious problems and impairments in the operation came from intense antiaircraft fire against U.S. helicopters, particularly the utility and cargo helicopters around and in landing zones (LZs). The NVA employed “hugging” techniques by getting in as close to ARVN units as possible, then waiting to engage helicopters on “short final,” when landing and again when departing LZs. The NVA also usually struck LZs with deadly mortar and/or artillery barrages. Too often resuppiy and troop insertion or extraction sorties could not be cornpleted, even with support of helicopter gunships, artillery, tactical air and B-52s. Although unplanned, ARVN units that were besieged on FSBs became like decoys used to set up the enemy for massive U.S. bombing, particularly by 8-52s. Such strikes took heavy tolls on NVA forces.

Even aeromedical evacuation (MEDEVAC) helicopters with their Red Cross insignias were not exempt from NVA antiaircraft fire. As the wounded and dead mounted without being evacuated, and as supplies ran low, on occasion ARVN units lost their integrity and were routed by the NVA. Some ARVN troops rushed to and overloaded landing helicopters in desperation to get aboard and return to Khe Sanh.

Despite problems created by the NVA, LAMSON 719 successfully met most of the operations objectives. But, it fell far short of what it could and should have been. Most ARVN units inflicted serious losses on the NVA and showed great valor against withering odds. In the mid-intensity conflict that LAMSON 719 was, significant losses of troops and equipment were inevitable. In the final analysis, ARVN troops, for the most part, were equal to or better than those of the NVA. Figure 1 summarizes the casualty statistics.

LAMSON 719 revealed some serious flaws in the U.S./ARVN war effort, particularly in the progress of the Vietnamization program. The ARVN force was not sufficient in size and a long way from being able to provide its own air and fire-LAMSON 719 power to thwart determined NVA aggression. Despite greater NVA losses, there were significant ARVN losses: The inability to extract all of their dead and wounded greatly damaged ARVN morale and the confidence of the South Vietnamese people and Army.

Army Aviation In LAMSON 719

For Army Aviation, LAMSON 719 proved the concept of airmobility beyond a doubt. The NVA was well-versed in the four employment principles of air defense: mix, mass, mobility and integration. However, Army Aviation countered enemy efforts more times than not. LAMSON 719 was the costliest airmobile assault in terms of loss of lives and equipment in the entire war; yet, measured against such intense antiaircraft fire in a mid~intensity battle, losses were remarkably low. In particular, about 80 percent of the aircraft shot down were lost in the immediate vicinity of “hot” LZs where helicopters were most vulnerable. Figure 2 portrays a summary of Army Aviation {lOlst} battle statistics.

LAMSON 719 produced several significant events in the history of Army Aviation that we should all be aware of:

- More helicopters received combat damage and were shot down during LAMSON 719 than at any other comparable time in the Vietnam War. Of the Army heiicopters committed to LAMSON 719, 68 percent received combat damage and 14 percent were lost.

- The combat assault on Tchcpone, some 26 miles into Laos, involved more helic0pters in a single lift than any combat air assault in Army Aviation history. On 6 March, 120 UH-1 Huey helicopters airlifted two battalions of ARVN troops from Khe Sanh to L2 HOPE in the assault on Tchcpone. An armada of helicopter gunships also participated.

- For the first time in combat, AH-1G Cobra gunship helicopters engaged enemy armor. During LAMSON 719, Army “CAV” gunships were credited with destroying six tanks and immobilizing eight more. More details about these armor engagements follows in later paragraphs.

- Two of the worst days in Army Aviation history occurred during LAMSON 719. On 3 March, in a helicopter assault to establish LZ LOLO. 11 UI-1-H helicopters were shot down in the immediate vicinity of the LZ and some 35 UH-ls received combat damage. On 20 March, attempts to extract ARVN troops out of LZ BROWN resulted in 10 UH-1H helicopters being shot down and some 50 more receiving combat damage; 29 percent of all UH-1H combat losses during LAMSON 719 occurred on those two fateful days, but Army Aviation still completed its missions.

| Killed in action |

Wounded in action |

Missing in action |

Equipment Lost (excluding aircraft) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. | 102 | 215 | 53 | (none in Laos) |

| RVN | 1,146 | 4,236 | 246 | 71 tanks |

| 45% casualty rate for committed troops in Laos. | 96 artillery | |||

| 278 trucks | ||||

| NVA | 14,000 | Unknown | Unknown | 100 tanks |

| Estimated 50% casualty rate. | 290 trucks | |||

| Figure 1: Casualty Statistics | ||||

| Aircraft | Total Aircraft |

Aircraft Damaged |

Damage Incidents |

Aircraft Lost |

Percentage Lost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OH-6A | 59 | 22 | 34 | 6 | 10 |

| UH-1C | 60 | 48 | 66 | 12 | 20 |

| UH-1H | 312 | 237 | 344 | 49 | 16 |

| AH-1G | 117 | 101 | 152 | 18 | 15 |

| CH-47 | 80 | 30 | 33 | 3 | 4 |

| CH-53 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 2 | 13 |

| CH-54 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| OH-58 | 5 | No Data | No Data | No Data | No Data |

| TOTAL | 659 | 453 | 644 | 90 | 14 |

| Figure 2: Helicopter damage and Loss Statistics | |||||

During LAMSON 719 the 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile) and units under its operatioual control (OPCON) lost 90 helicopters. Also, five Army fixed wing aircraft were lost, plus two ARVN helicopters. U.S. Air Force, Navy and Marine losses were given at eight aircraft. Not surprisingly, unofficial estimates published by the news media listed the damage and loss statistics higher: 600 and 107, respectively.

During the 45 day operation some replacement aircraft were received and other aircraft lost for maintenance (scheduled rebuilding, etc.) or noncombat accidents. So, the number of helicopters involved had to vary. The 101st established a data base by unit and tail number for the aircraft initially employed in the battle. From this data base. the aviation statistics summarized here are considered highly accurate. Nevertheless, even if higher estimates of helicopter losses and battle damage were more accurate, the survivability of helicopters in the mid-intensity, high antiaircraft threat environment of Laos would still be most remarkable.

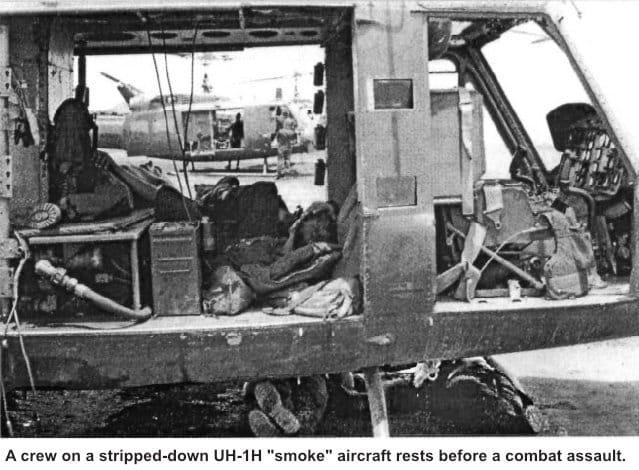

In the 45 days of combat flying in support of LAMSON 719, 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile) and OPCON units logged a total of 78,968 flying hours and completed 204,065 sorties. For the 101st, 426 helicopters logged 28,836 hours in February (68 hours per airframe) and 31,067 hours in March (73 hours per airframe). There was a daily average of 161 aircraft flying, involving 575 aircrewmembers.

During LAMSON 719 aircrewmembers were waived from a restriction to fly no more than 140 hours in a 30-day period. It was not uncommon to find aircrewmembers with some 300 combat flying hours during LAMSON 719. Indeed, Army Aviation displayed a truly heroic level of mission integrity on a daily basis. Anyone who flew the LAMSON 719 gauntlet in Laos learned how serious a war can become as compared to what came to seem like almost routine low-intensity conflict, as otherwise experienced in South Vietnam.

Casualties of the 1015t Division over the 45 day period are listed as: 26 killed in action, 152 wounded in action and 32 missing in action. This is an average of 4.7 aircrewmember casualties per day. For every 1,000 hours flown, slightly more than five aircrewmembers became casualties. For every 1,000 sorties in Laos there were five casualties compared to less than two casualties per 1,000 sorties in South Vietnam for the same period. Also, in Laos, two aircraft were lost per 1,000 sorties, which compared as a 13 times (13X) greater damage incidence than occurred in South Vietnam for the same 45-day period.

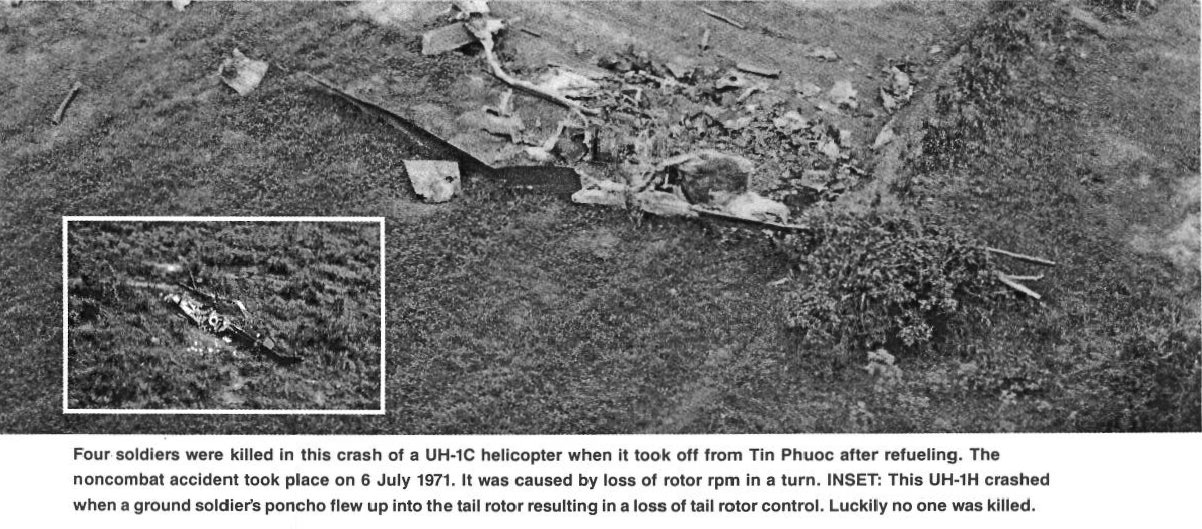

One area of especially interesting statistics is the noncombat accident rates. During LAMSON 719, 11 helicopter accidents were reported, representing a rate of 29.0 accidents per 100,000 flying hours. In the same period a year earlier, the lOlst experienced an accident rate of more than 40 accidents per 100,000 flying hours. For all of Vietnam, the Army Aviation accident rate in fiscal year (FY) 1970 was 23.3 accidents per 100,000 flying hours; in FY 71 the accident rate was 19.0. Compared to the current Class A through C overall accident rate of 8.81 for FY 85 per 100,000 flying hours, Army Aviation has indeed come a long way in aviation safety.

It’s appropriate to point out some other statistics about Army Aviation in Vietnam. The U.S. Army Aviation Center estimates that some 13,000 Army aircraft cycled through Vietnam from 1961 to 1973. Of all these aircraft, nearly 6,000 were totally lost due to combat or noncombat accidents. From 1968 to 1971, for instance, 4,510 rotary wing aircraft were lost: 2,879 (64 percent) to combat and 1,631 (36 percent) to noncombat! In the same period, 499 fixed wing aircraft were lost: 292 (59 percent) to combat and 207 (41 percent) to noncombat! These numbers are not exaggerated. Think about it – nearly 40 percent of the aircraft lost in Vietnam were not down as a result of combat action!

The mission of the Army Medical Department is to “conserve fighting strength.“ While it’s not polite to steal, it is also accurate to say that the mission of Army Aviation’s safety and maintenance programs is to “conserve fighting strength.” During the Vietnam War, the single most significant “combat multiplier” Army Aviation could have taken advantage of was in the area of aviation safety. Field Manual 101-5-1 “Operational Terms and Symbols,” defines a combat multiplier as a supporting and subsidiary means that significantly increases the relative combat strength of a force while actual force ratios remain constant. A greater emphasis on aviation safety could have magnitudinally increased the relative combat strength of the Army Aviation force in Vietnam. opefully, we have learned that and will not let aviation safety slip away in future conflicts.

During the Vietnam era, an estimated 22,000 helicopter pilots were trained by the Army and served at least one tour in Vietnam. From 1961 to 1971, 1,103 aviators were listed as killed in Vietnam from all causes. Official Army casualty statistics listed a loss of 1,045 aviators killed due to combat and non-combat aviation mishaps over the period 1 January 1961 to 30 June 1979. From these statistics, 618 {59 percent) were due to combat and 427 {41 percent) were due to non-combat accidents. Hence, several different statistical sources are in fairly close agreement in both combat and nonconibat personnel and aircraft losses.

In LAMSON 719, however, the ratio of accidents to total losses for helicopters was much lower (14/104) at 13 percent. This was attributed to a greater “vigilance” by aviators in the high threat environment. Most accidents that did occur were attributed to aviator “let down” away from the combat environment.

The unsung heroes of LAMSON 719 had to be Army Aviation maintenance and logistical support people. Remarkably few aircraft were lost due to mechanical failures and “operational readiness” levels remained fairly high for most units throughout LAMSON 719. This is even more remarkable considering that most units OPCON to the 101st operated out of field sites without the benefit of proximity to intermediate and higher maintenance levels.

Lessons Learned From LAMSON 719

The list of lessons learned, taken from the 101st reports, do not flow together, so each area is introduced by helicopter silhouettes.

During LAMSON 719, combat assaults were primarily planned on intelligence pertaining to antiaircraft locations rather than enemy troop concentrations. Employment of air cavalry units in reconnaissance to gather current intelligence in advance of combat assaults was found to be critical for screening flight routes and pickup zone and landing zone sites in Laos. Sensor implants also were found to be effective in identifying neutralization, suppression, avoidance and probable safety zones.

The most critical factor to the success of all aviation Operations in the mid-intensity environment was considered to be thorough, detailed planning. Because of the high density and effectiveness of antiaircraft fire, it was imperative that all missions be executed swiftly, precisely and efficiently. All available assets had to be employed for each operation. For instance, MEDEVAC helicopters rarely made extractions without two gunships for fire suppression support. Toward the end of LAMSON 719 aeromedical evacuation missions used four gunships whenever possible and coordinated a second “Dustoff” or “slick” (UH-1H} helicopter for high-ship support and downed aircrew recovery.

Planning for refueling and rearming points caused a lot of problems because they were not given the priority they deserved. They usually lacked suitable areas for approach, departure and hovering maneuverability, and on occasion they were unable to accommodate the large volume of aircraft. Priority planning was essential since mission delays in the mid-intensity tactical environment were always costly.

Marginal weather was a problem throughout the LAMSON 119 area of operation. Multiship combat assaults required greater planning still, and more flexibility in adverse weather:

- Aircraft had to be ready without delay.

- Continuous weather checks were essential.

- More detailed map planning with suitable time to conduct route reconnaissance and to complete air movement tables was needed. The above were considered critical for successful multiship combat assaults.

VHIRP (vertical helicopter instrument (IFR) recovery procedures) were unheard of at the time. Most aviators were not proficient in instrument flight rules. There were no radar controllers; the few navigational aids on the coast were unreliable; and most aviators did not have approach plates nor did they know approach procedures. If an aircraft inadvertently entered instrument meteorological conditions the general procedure was to climb to 5,000 feet above ground level or try to get “VFR (visual flight rules) on top” of the clouds; look for a “hover hole” to descend back to ground level; or fly east at least 30 minutes to get over the South China Sea, the descend with your fingers crossed.

Effective recovery of downed crews, and aircraft when possible, had to be accomplished without delay to be successful. Delays usually resulted in large-scale operations and tactical air support to recover crews. Some aircrew recovery operations were conducted by U.S. Air Force search and rescue teams tlying armored-plated CH-53 helicopters. Recovery plans for downed crews and immediate “high-ship” assets (usually an unloaded UH-1H) flying above the mission aircraft, along with the command and control (C&C) aircraft, were considered essential.

On some occasions aviators attempted to fly damaged aircraft out of Laos rather than electing to land in a secure area. This resulted in the loss of at least four aircrewmembers. Aviators were encouraged to put aircraft on the ground whenever any difficulties arose. Just as a humorous note here: The 101st report stated that, “Crewmembers’ fears of setting down in hostile territory were alleviated by ensuring they were knowledgeable in survival, escape and evasion (techniques).“ This statement was optimistic at best. Most aviators viewed any downtime in Laos as their being worse off than a fish out of water.

During LAMSON 719, hydraulic failures and engine failures caused some problems for aircraft availability. Several solutions were offered for maintenances use, but the most interesting was a recommendation to place a form in aircraft logbooks for keeping “daily engine recording” (DER) checks to compare engine performance. DER checks were the precursor to the engine “health indicator tests” currently performed in Army aircraft.

The sharp increase in damage to helicopters created an increased demand for unscheduled maintenance, especially for sheet metal, prop and rotor, and electronics and avionics repairs. Maintenance activities were required to operate 24 hours a day and were augmented at all levels as much as possible. Controlled cannibalization on retrograde or unserviceable aircraft greatly reduced supply needs; stockage of such quick change assemblies as engines, rotor blades and heads, transmissions and tail booms markedly decreased turnaround time for getting aircraft back into the battle. In some units an aircraft commander, crewchief and gunner habitually flew one aircraft. Whenever possible, when the aircraft went down for scheduled maintenance the crew went down with it and assisted in the maintenance work.

Communications security was a serious problem. The ARVN lost more than 1,500 radio sets in Laos. In the latter part of the Operation a call to a field location to “pop smoke” (with a colored smoke grenade) would frequently result in many locations popping smoke. ARVN and NVA troop concentrations were extremely difficult to distinguish except on fire support bases in Laos. Frequently, field units had to use smoke grenades (or other means) at least twice to verify their locations. On at least one occasion (witnessed by the author) an aircraft and its crewmembers were lost when a C&C aircraft failed to properly verify an LZ which turned out to be an NVA ambush.

There were serious problems with secure communications between aircraft and United States’ ground units. ARVN units did not have secure radio capabilities. Only FM (frequency modulated) radios had secure capabilities in some aircraft and they were usually not set properly for each day’s frequencies. Implementing frequency changes for security initially caused problems because such changes were made at 2400 hours. This caused units to have to violate strict light and noise discipline. Frequency changes were later changed to occur at first light. It’s safe to say that, from the first day to the last, communications security by U.S. and ARVN forces was terrible; that of course was an advantage for the NVA.

Air cavalry teams employing scout aircraft to locate the enemy. usually by drawing fire, were generally unsuccessful and this procedure was abandoned as a tactic in Laos. The most successful teams consisted of one AH-lG low, and two or three AH-G helicopters high, with one UH-1H for C&C and downed crew recovery. The principal reason cited for this was the vulnerability of the scout aircraft because they did not have an immediate fire suppression capability. A serious emphasis was placed on the need for scout aircraft to have some fire suppression capability. Of course, the mast mounted site on the new OH-58D (AHIP) scout helicopter does afford a greater standoff range to conduct reconnaissance missions against threat forces.

During LAMSON 7l9, Army Aviation gunship helicopters were not well-equipped nor prepared to engage NVA tanks. While Army AH-1Gs were credited with destroying six tanks and immobilizing eight, there were actually 66 sightings reported. The NVA had PT-76 and T~54 tanks. Only thin skinned PT—76 tanks could be engaged because Cobra gunships did not carry or even have available, armor piercing ordnance. When tanks were spotted by gunships the AH-ls rareiy had enough ordnance to engage more than one or two. In the most effective tank engagements, Army helicopters located and fixed targets, then turned them over to tactical fighter-bombers. During LAMSON 719, tactical air support was frequently available on short request, usually within 15 minutes, although low ceilings and poor visibility greatly limited their support in Laos.

Enemy hugging tactics, plus a large dispersion of high troop pepulations concentrating small arms and heavier weapons antiaircraft fire, cannot be suppressed easily by aerial or ground artillery. Even though there was not an enemy aviation threat, antiaircraft engagement discipline of the NVA was effective enough to create some “no go” terrain for Army helicopters.

On a deep attack in a mid—intensity conflict the accomplishment of Army Aviation missions takes on an even greater significance, especially for such missions as resupply and acromedical evacuation. MEDEVAC assets were not adequate to handle the high number of casualties. For moral purposes and troop morale it is just as important to evacuate the dead as well as the wounded &ndash on the same helicopter if need be. This was a particularly acute problem with the South Vietnamese because their cultural tradition emphasized close familial ties.

Cargo helicopters were more limited than other helicopters in their ability to complete sorties in the mid-intensity environment of Laos. The fact that cargo helicopters were not able to resupply critically needed artillery ammunition and other supplies to ARVN FSBs played a significant part in limiting the duration and the success of LAMSON 719 operations 0n the ground for the ARVN in Laos.

While multilift, tight formation combat assaults were typical within South Vietnam, such tactics were disastrous in the mid-intensity environment of Laos. The most successful assaults were by single-ship formations with 30-second separations.

Most unit operating procedures called for en route flights in Vietnam to be conducted at 1,500 feet above ground level (AOL) and at least at 3,000 feet AGL in Laos. Low level or nap-of-the-earth (NOE) flying was still officially prohibited, even during LAMSON 719; but it was used much more frequently as antiaircraft fire intensified. Comments about NOE flight in the afteraction report are particularly interesting and directly quoted here: “Under certain circumstances combat assaults, resupply missions, and medical evacuation were better conducted by low level, nap-of-the-earth flight than by high altitude flight.

Aircraft flying the nap-of-the-earth presented fleeting targets to enemy gunners and gained surprise by their sudden and unexpected appearance in the landing zone and quick departure. When this tactic was used, a guide aircraft flew at a higher altitude above the low-flying aircraft to vector them to their objective. Nap-of-the-earth flight was sometimes appropriate and effective when aircraft flew into a firebase or friendly position surrounded by enemy who used “hugging” tactics and placed accurate fire on the landing zone or when low cloud ceilings forced pilots into choosing between flying the dangerous intermediate altitudes or at treetop level. Nap-of-the-earth flight was not used frequently.“

No doubt the author of the paragraph above felt compelied to add the last sentence to dilute any sanctioning of low-level flying. Interestingly, after LAMSON 719 most lOlst and OPCON units returning to their previous areas of operations and missions in South Vietnam resumed using the earlier tactics of tight formation combat assaults and were still prohibited from flying NOE. But, LAMSON 719 had converted a great many aviators who flew NOE as often as possible, especially on single ship resupply missions. While NOE techniques were not officially recommended in the afteraction reports, LAMSON 719 probably did more to move Army Aviation tactical doctrine toward such techniques (as we currently employ and as were being developed before Vietnam) than any other operation in the war.

Personal Reflections

Editor’s note: CPT Fuibrook conciudes this three-part cowerage of LAMSON 719 by offering (below) his personal reflections on the values of the lessons {earned by Army Aviation in LAMSON .719. His thoughts, pins those of others who reviewed this series on LAMSON 719, will be published in an Aviation Digest earty this winter. That gives you a chance to participate with us in the LAMSON 719 review arttcie. You don have to be a LAMSON 719 vet. Your functional thoughts about this series of articies, or of other LAMSON 719 opinions or thoughts, iso are weicome. Send them to Editor, Aviation Digest, R0. B 699, Ft. Rucker, AL 36362~5 00. Piease send them not later than 1 November 1986. Your thoughts are very important!

Nothing I‘m about to write is representative of any official policy of anybody or any organization beyond me (although I believe most Vietnam-era aviators will strongly agree with most of my observations).

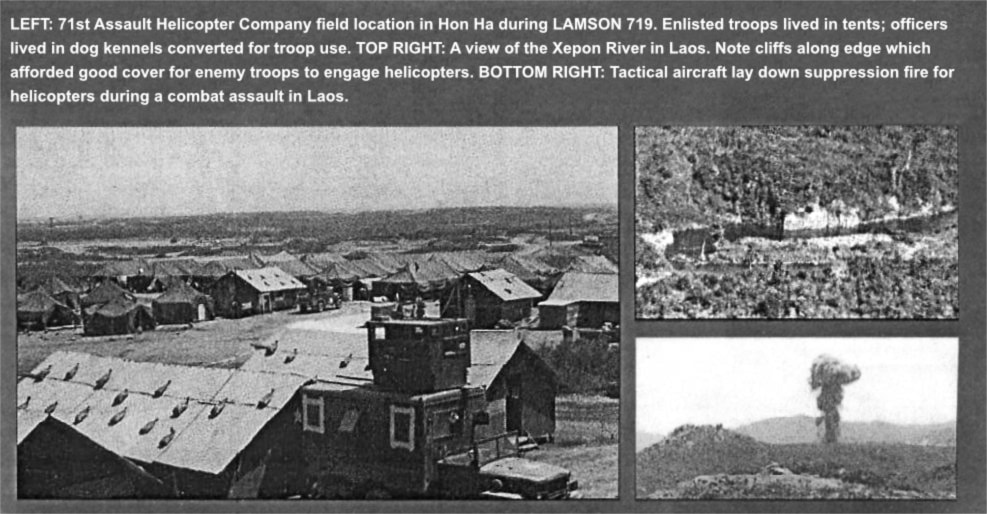

I served in Vietnam as a warrant officer from May 1970 to June 1971. I was assigned to the 71st Assault Helicopter Company (AHC), flying UH1-H helicopters out of Chu Lai, a city south of Da Nang, in the northernmost corps region of South Vietnam. The 71st AHC supported units of the America], or 23d Infantry Division.

During my tour I logged 1,420 hours of combat flight time. In all that time I took “hits” from enemy fire on only one occasion: On 6 March 1971, as Chalk 47, on the 120-heIicopter assault to Tchepone in Laos. In my unit I was one of the highest time aviators with the least number of hits among the area of operations (A0) pilots. Aside from a little bit of luck, the reason for this was because I flew low level anywhere and everywhere, every chance I got. On several occasions, superior officers threatened to take my aircraft commander (pilot in charge) orders because I was a “cowboy and unsafe.” Admittedly, at the time I was a young whipper snapper, undaunted by threats. After LAMSON 719, however, many pilots who routinely flew low level were to a large degree vindicated. NOE flying techniques were officially reinstituted to aviation training around 1975. Actually NOE flight tactics were being developed at the Aviation Center, Ft. Rucker, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but were somehow dropped during the Vietnam era.

The rest of this section consists of reflections that I beiieve are worth passing on to other aviators and to Army planners.

If we are ever called upon to do the jobs we are trained for in combat, it’s important to realize how much more a part of “living history” each of us becomes. Whiie I was in Vietnam I took several hundred photographs with a 35 mm camera, but that wasn’t enough. I wish I had done more. Remember: Save! Save! Save! Keep a daily diary. Have family members save and return your letters. Keep track of names and addresses of your compatriots and file important documents and maps. Collect patches and other memorabilia they all will mean much more later on, even though it may not be apparent now.

When you are under fire in a mid-intensity battle, there is no time to read a map or thumb through a CEOI (Communications-Electronics Operation Instructions) looking for radio frequencies and call signs. A good AO pilot memorizes a map in less than a week. When an aviator is given a mission sheet it includes at least one frequency and call sign. In a high threat environment if proper communication and LZ confirmation cannot be established the sortie should be aborted. This does not mean that aviators should be cavalier, dogmatic or uncooperative with the units supported. The highest value anyone can subscribe to in combat is “mission integrity.“ Use your usually superior radio communications capabiliities and command training and experience to effect better coordination in the rear area. This enables missions to move smoothly where it can count the most–in battle.

Generally, there are two types of aviators when bullets start flying. All of us experience a lot of anxiety, but some have a facilitating anxiety and actually fly more precisely. Others have a debilitating anxiety and overtorque or overcontrol their aircraft in an instant. You can never distinguish aviators with the debilitating type of anxiety until they actually get into a serious combat or emergency situation. Once such aviators are identified, and if they must remain as A0 pilots, they are better off being copilots, and being purposely paired with aviators who do well under pressure.

All of us respond differently to anxiety in combat, regardless of our type. During the few occasions when I truly feared for my life (all of which occurred in Laos during LAMSON 719) l was paticularly calm and confident. yet, away from the danger, I quivered so badly the copilot had to take the controls. Upon returning to the combat situation a short time later I almost instantaneously regained my composure. A copilot you are confident with makes an even greater difference in combat. Make no mistake, combat is quite exhilarating.

During my tour in Vietnam I had two unit commanders–the best and the worst commanders I have known. The importance of the commander for unit morale and effectiveness, especially in combat, cannot be overemphasized. One serious problem arose in the selection of pilots in command (PICs). The good commander allowed the PICs of each platoon to select when their copilots would be given PIC status. Three months incountry and at least 300 flying hours were requirements. The “other“ commander personally selected PICS and made all commissioned officers PICs and flight leaders regardless of their experience. One captain with less than 1 month incountry was at the controls leading a flight into an LZ when enemy fire was taken. The inexperienced aviator immediately overtorqued the aircraft, requiring a major powertrain overhaul. The other commander, himself on another mission, stretched the few bolts that attach the tailboom to the rest of a UH-1H by habitually flying out of trim when trying to be an air mission commander. There are more stories: some real horror stories that end tragically. But the point is that poor commanders demoralize and reduce combat effectiveness of even previously superior performing units–and they do it in a hurry! If you are fortunate, a good subordinate leader can take charge and help restore unit integrity.

In developing its weapon systems, Army Aviation places greatest emphasis on types and sophistication of Communist air defense assets and helicopter air-to-air capabilities. This is fine, but the highest probability for future battles is at the low-intensity level where such weapons will be less of a factor. I contend, however, that regardless of the adversary or the level of conflict, in any future battles more aircraft (especially helicopters) will still be lost to small arms fire than to any other weapon system. Foot soldiers or terrorists and their rifles will continue to be Army Aviation’s most serious threat. This will be even more applicable to fluid battlefields where small unit terrorist cells could attack targets anywhere.

Let’s not forget that on the battlefield foot soldiers make the greatest difference. Only they can effectively take, hold and control terrain. In current air-land battle doctrine Infantry, Armor and Field Artillery soldiers would not do so well without Army Aviation, the newest member of the maneuver arms. But, neither can Army Aviation succeed without the integral efforts of the combined arms team. The principal mission and duty of Army Aviation remains: To assist the maneuver force to accomplish its objectives by serving at all levels as combat, service and support arms of the combined arms team!

I believe the most significant combat multiplier in the Vietnam War was civil-military affairs. Understanding the cultural influences and characteristics of the people is critical–they are every bit as important as knowing the terrain, especially in a low–intensity conflict. We could win every major battle then lose the war by failing to win the hearts and minds of the people we seek to defend, and by lacking the advocacy of Americans who must support us.

Unfortunately we failed to inform the American public, and as a result most soldiers who went to Vietnam were not aware in the purposes and objectives of the war. We served in Vietnam to protect the freedoms of a nonviolent, communal culture against countercultural. oppressive and atheistic force. We were the country that could save the “wimp from the town bully.“ Our purpose was honorable and justifiable – but somehow we lost sight of it.

Most people are not aware of the significant impact the culture of the Vietnamese people had on daily military operations. l’ve been to the Aviation Officer Advanced Course in the past year, and i have talked to many of the instructors of the Officer Basic, Precommand and Warrant Officer Career Courses. The content of these courses is excellent, but there is a noticeable deemphasis or failure to recognize the importance of civil-military affairs and culture or demography (loosely, the geography of people) and how they influence military operations. This is particularly true in the intelligence planning of the battlefield process where such factors are not even given a sentence’s worth of lip service.

Simply put, the more one knows about the Vietnamese and their culture, the easier it is to understand the Vietnam War. I’m sure that soldiers who fought in Korea, Lebanon and Grenada would agree with me about how important civil-military affairs are to the success of military campaigns.

In these last three issues of this magazine I have attempted to provide a “peek” through a small window at Army Aviation’s first sustained and significant encounter with mid-intensity combat-LAMSON 719; there is much more that many more people could bring up about (specifically) the value of Army Aviation airmobile/air assault lessons learned in LAMSON 719, and (generally) how they relate to other developments in air assault tactical doctrine. As stated, the Aviation Digest is ready to print functional comments from reviewers and readers. Send in your thoughts–you’ll be doing our branch a favor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author gratefully acknowledges the contribution of photographs by CW4 Doug Womack. CW4 Mike Harbin and CW4 Bob Hench. Also, the photographic section at the U.S. Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory was a great help in reproducing some of the photographs for publication. In addition, the author appreciates the encouragement received from Captains Mike Moody and Dave Wabeke of the Directorate of Combined Arms Thaining at the Aviation Center for developing the LAMSON 719 series beyond the state of anecdotal war stories to that which you have beiore you.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

After Captain Jim E. Fulbrook returned from Vietnam in 1971 he continued his Army Aviation career until 1981 as a reserve warrant officer aviator in the Delaware and New Jersey Army National Guard units. He completed a BA degree in psychology from Glassboro State College, and MS. and PhD. degrees in biology at the University of Delaware. Dr. Fulbrook’s academic background is in vision research and neuroscience. In 1981. he received a direct commission to captain in the Medical Service Corps and returned to Active Duty serving as a research scientist in the U.S. Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory. Ft. Rucker, AL. Captain Fulbrook also is a Master Army Aviator with more than 3,000 flying hours and holds an instructor pilot rating. Recently. he completed aviation refresher training and the UH-60 Black Hawk transition for assignment as an aviator in an aeromedical evacuation unit in Germany.

Captain Fulbrook is continuing to assemble references and information for further articles about LAMSON 719. Anyone who participated in LAMSON 719 and has information. photographs. negatives or other memorabilia they can share (all returnable) please contact: Captain .Jim E. Fulbrook. 236th Medical Detachment, APO NY 09178. In particular, information is being sought about the “Witch Doctor Six“ incident and on corroborating statistics on the battle in general.

This article is Part 3 from a three part series that was written by our own Rattler 20, Captain Jim E. Fulbrook, Ph.D., MSG and published in the United States Army Aviation Digest in June, July and August of 1986.

Webmaster note: This article refers to the operation as “LAMSON 719”. The correct name of the operation is actually LAM SON 719, referring to the birthplace of a Vietnamese hero who led an army to expel the Chinese from Vietnam in the 15th Century. The use of “719“ signifies the year “1971“ and the battle area along Route 9. Also noteworthy is the fact that the scan of the articles was less than optimal, several of the images in the article were unusable. You can see the original scanned documents here.