Aviation Digest LAMSON 719 Part 2

This article is Part 2 from a three part series that was written by our own Rattler 20, Captain Jim E. Fulbrook, Ph.D., MSG and published in the United States Army Aviation Digest in June, July and August of 1986.

Webmaster note: This article refers to the operation as “LAMSON 719”. The correct name of the operation is actually LAM SON 719, referring to the birthplace of a Vietnamese hero who led an army to expel the Chinese from Vietnam in the 15th Century. The use of “719“ signifies the year “1971“ and the battle area along Route 9. Also noteworthy is the fact that the scan of the articles was less than optimal, several of the images in the article were unusable. You can see the original scanned documents here.

The Battle

LAST MONTH “Part 1: Prelude To Air Assault presented a review of the history of the Vietnam War leading up to LAMSON 719, the most significant airmobile/air assault battle of the war, and the only historical example of contemporary Army Aviation operating in a mid-intensity conflict. Part I defined the levels of conflict. It also described Army Aviation missions and units, concepts of fire support bases, and airmobility in the Republic of Vietnam.

Part 11 describes the immediate events leading up to LAMSON 719 the operations order, the battle itself and the battle statistics. Next month, Part III will conclude with a review of battle statistics and discuss some reflections and values of lessons learned from LAMSON 719 and from the U.S. military involvement In Vietnam in general.

The Ho Chi Minh Trail

After North Vietnam lost the use of the resuppiy port at Kompong Som in Cambodia in 1970, all supplies and reinforcements had to be brought down the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Laos. With the successful offensive of U.S. and South Vietnamese troops into Cambodia, also in 1970, the North Vietnamese Army {NVA} had to dramatically increase activity on the Ho Chi Minh Trail to try to reconstitute their forces in the south.

Even though the Ho Chi Minh Trail network had been continually bombed for years, by late 1970 the Communist supply system had been greatly improved. The trail system spread out over Laos like a spider web of between 3,500 to 8,000 miles of roads and trails. More than 150,000 Communist volunteers, soldiers and forced laborers built and maintained the trail system. During this time some 5,000 to 14,000 trucks traveled along the trail network usually at night to avoid detection. The North Vietnamese even had a 4-inch fuel pipeline that ran from North Vietnam as far south as the A Shau Valley.

The trail system was divided into command centers, transshipment points, base areas and way stations which were called “binh trams.“ Each binh tram operated as a complete logistical center with its own area of responsibility. Binh trams had medical, engineering, storage, transportation and maintenance support as well as infantry and antiaircraft troops to provide secur1ty.

The Ho Chi Minh Trail was further divided into three routes. Trucks only carried heavy supplies and went on one route. Light equipment and supplies were carried by people, bicycles and animals on another route. Combat troops marched on foot on still another route, often in troop strengths as high as 600 peopie. It could take foot soldiers up to 100 days to reach their destinations in South Vietnam. Depending on the type of route, each binh tram was located a day’s movement apart. The two largest Communist base areas found along the Ho Chi Minh Trail were designated “604” and “611”: These became the principal targets of the LAMSON 719 operation.

The Laotian panhandle experiences two seasons each year. Most supplies were moved along the Ho Chi Minh Trail in the dry season from October to March. For the rest of the year monsoon rains severely limited traffic.

All of the factors of season, troop and supply buildup on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and willingness to incur into Communist territory, as demonstrated by the U.S./South Vietnamese Cambodian offensive, were common knowledge to both sides. The Communists expected an attack into Laos. But, rather than abandon their base areas and supplies to avoid a decisive defeat, as they did earlier in Cambodia, the Communists upgraded their defenses and troop strength to stand and fight. By the end of 1970, an estimated 18,000 additional combat troops, including 20 antiaircraft battalions, were sent to Laos to reinforce base areas 604 and 611. These units were equipped with several hundred 12.7 mm (50 caliber) and 14.5 mm antiaircraft guns; 23 mm cannons; and 37 mm, 57 mm, 85 mm and 100 mm anti-aircraft assets among an estimated 3,000 prepared emplacements over the Laotian panhandle.

In the mountains and jungles of Laos there were few sites suitable as helicopter landing zones (LZs). The North Vietnamese triangulated these clearings and much of the high ground with antiaircraft weapons, and preregistered their mortars and artillery to zero in on the potential LZs. By the end of 1970, North Vietnam had three infantry divisions, two artillery regiments, and one armor regiment in the 604/611 base areas, with eight additional regiments available within 2 weeks as reinforcements from other areas.

The Americans and South Vietnamese were alarmed by the serious buildup of activity along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Intelligence reports indicated that the North Vietnamese were planning offensives against Cambodia and several provinces of South Vietnam at the end of the dry season. A preemptive strike was tempting and a risk worth taking. The South Vietnamese and Americans had turned the war around and were on the offensive. In December 1970 the U.S. proposed an offensive which was quickly approved by the South Vietnamese. Joint planning for LAMSON 719 began in January 1971 with bareiy a month to work out operations plans and to prepare units.

The principal obectives of LAMSON 719 were to interdict and disrupt the flo of enemy troops and supplies into South Vietnam along the Ho Chi Minh Ttail in Laos. LAMSON 719 would be the first major test of the Vietnamization effort. No American ground combat troop or advisors would accompany the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) in the attack against the Ho Chi Minh Trail. LAMSON 719 ould be the greatest test of airmoility/air assault and fire suppor base (FSB) concepts. It would hopefully cripple North Vietnam’s ability to launch any offensivs and buy more time and safety for the continued withdrawal of U.S. troops. And, hopefully, it would enhance peace negotiations which were already underway.

LAMSON 719 Operations Plan.

The operations plan proposed four phases.

Phase I called “Dewey Canyon II,” would be a U.S. operation to reopen the base at Khe Sanh and clear Route 9 up to the Laotian border.

Phase II would be an ARVN infantry and armor attack down Route 9, with northern and southern attacks to establish FSB protection on the flanks. The Phase II objective was the town of Tchepone, some 40 kilometers or nearly 25 miles west into Laos. The operational area was 10 to 20 miles wide from north to south, closing in on Tchepone.

Phase III would be the exploitation phase when ARVN troops would fan Out to conduct search and destroy operations against enemy troops and bases.

Phase IV involved the orderly withdrawal of ARVN troops from Laos. The operation was to last up to 90 days or until the onset of the rainy season.

Although the term was not mentioned in afteraction reports, LAMSON 719 was to be an airmobile “deep battle” or attack, wholly dependent on U.S. helicopter support for resupply and troop insertions and extractions. FM 101-5] defines a deep battle as all actions that support the friendly scheme of maneuver an: which deny to enemy commanders the ability to employ their forces (not yet engaged) at the time and place, or in the strength of their choice.

LAMSON 719 also was to be the most significant “combined operation” in the Vietnam War because U.S. advisors would not accompany the ARVN troops in Laos. FM 101—5-1 defines a combined operation as an operation conducted by forces of two or more allied nations acting together for the accomplishment of a single mission. In previous U.S./ARVN operations, U.S. advisors usuall served as fire and air support coordinators, and frequently served as command and control in air assaults with U.S. helicopters. In support of LAMSON 719. the United States would commit more air and artillery support to a single battle than at any time during the Vietnam War.

The ARVN units were supported by U.S. Army units of the 24th Corps, but principally, and for all aviation operations, by the lOIst Airborne Division (Airmobile). Nearly 700 helicopters and 2,000 fixed wing aircraft were committed to the battle. Estimates ranged as high as 50 percent of U.S. air assets in South Vietnam being committed to the operation. The total American force numbered about 10,000 troops consisting of the equivalent of about six combat aviation battalions, four infantry battalions, three artillery battalions and battations of mechanized infantry, engineers, military police and other support personnel.

The ARVN force involved nearly 20,000 troops containing about 42 battalion-size units, 34 of which were committed in the Laos operation. These units included the ARVN Airborne Division, a Marine division, the lst Infantry Division, the 1st Armor Brigade and the lst Ranger Group. These were the elite of South Vietnam‘s Army, leaving only about a battalion in their entire national reserve.

Phase I: Dewey Canyon II

Phase I was launched on 30 January 1971 with brigades of U.S. mechanized infantry clearing Route 9 and an infantry brigade quickly securing the Khe Sanh area in a helicopter assault. Little opposition occurred and in a few days the airstrip was repaired and artillery units dug in. During this time the ARVN units assembled in the Khe Sanh area and prepared for the attack.

Phase II: The Attack

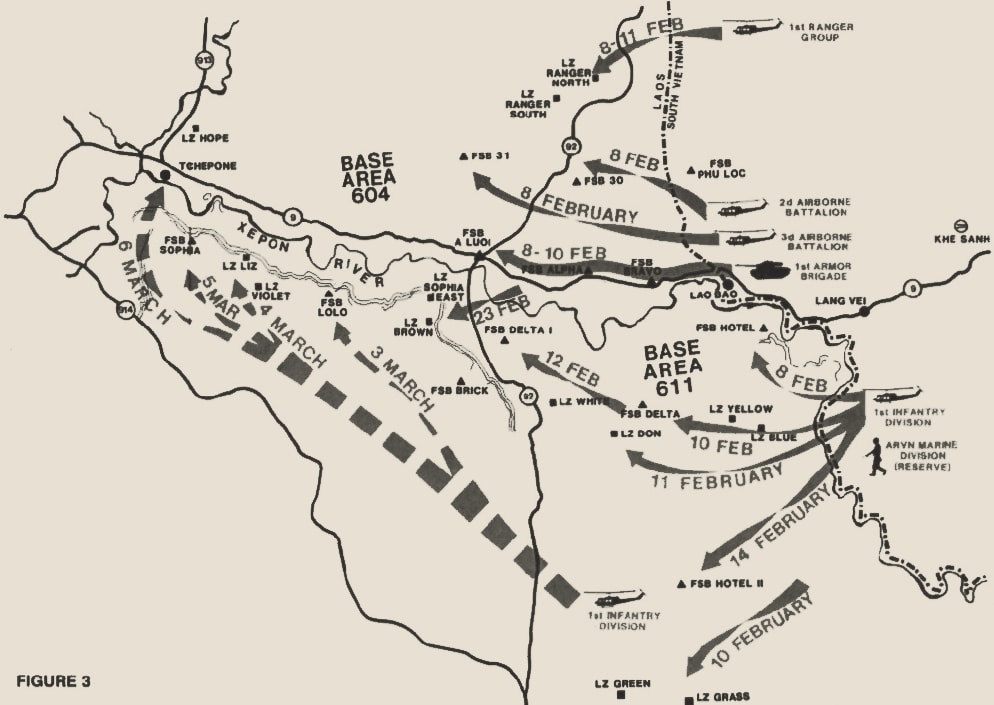

The ARVN attack into Laos began on 8 February and consisted of three main thrusts (maneuvers can be followed by referring to figure 3). Several battalions of armor and infantry, pius an engineer battalion, crossed the border into Laos on Route 9. Several units from the lst Infantry Division were helicopter assaulted south of Route 9 to establish FSBs HOTEL and DELTA on 9 February. North of Route 9, airborne and ranger units were helicopter assaulted to establish FSBs on LZs 30, 3] and RANGER SOUTH. Only the RANGER SOUTH assault received significant antiaircraft fire, quite possibly because nearly a dozen B—52 bomber strikes were made before the attacks and dozens of helicopter gunships assisted in the attacks.

On 10 February, a helicopter assault landed an airborne battalion on Route 9 at Ban Dong and established an FSB namecf A LUOI. Later that day the armored column reached A LUOI, which was halfway to the objective–Tchepone. From this point on, enemy resistance and antiaircraft fire began to increase on a daily basis. A number of helicopters were shot down from the 10th through the 13th of February as FSBs were set up and bolstered on 30, 31, A LUOI, RANGERS NORTH and SOUTH, HOTEL, DELTA and DON.

Phase III: Exploitation

For nearly a week, units of the lst Infantry Division on the southern flank conducted Phase III Operations searching out and destroying enemy-troops and supplies. Virtually everywhere the ARVN troops went they found supply caches and the bodies of enemy soldiers killed by U.S. air strikes. Several other FSBs and LZs were established on the escarpment as far west as DELTA 1. Unfortunately, the armored column did not move. This took away valuable time that the ARVN forces needed to react and allowed the Communists the advantage of more time to counteract. On the northern FSBs, ranger and airborne units became more and more decisively engaged. Helicopter assaults to L2 GREEN in the south were broken off because of intense enemy antiaircraft fire, and ARVN forces around LZ GRASS were in continuous enemy contact.

By 19 February the North Vietnamese had reinforcements in place. Large numbers of troops and trucks were seen in the northern area converging on the ranger bases, which had both come under serious attacks. Intense allied air and artillery strikes hit the enemy around the beleagured ranger positions. But, by the morning of 20 February the enemy was so close to the wire perimeters of RANGER NORTH that helicopter landings were tenuous at best. Attempts to resupply and medical evacuate troops from RANGER NORTH resulted in several helicopters being Shot down. That afternoon the base was overrun. Three days later RANGER SOUTH was abandoned before it too would have been overrun.

The ARVN lost nearly 300 troops in the defense of the RANGER FSBs, but a much greater toll had been taken on the enemy (more than 600 killed). Using ranger and airborne units on the northern flank was a tactical error. These units were light infantry and did not have the firepower that the ARVN Ist Infantry Division possessed. While the rangers were beaten, they showed remarkable courage and tenacity in defending for as long as they did against rocket, mortar, artillery fire and “human wave” attacks.

From 23 February to 2 March the airborne units on FSBs 30 and 31 bore the brunt of the North Vietnamese counterattacks. ARVN infantry forces to the extreme southern positions also were under increased enemy pressure. By the end of February several units were extracted from the southern bases (HOTEL II and GREEN) and redeployed by helicopter farther west on the escarpment to DELTA 1 and BROWN. On 27 February an airborne battalion was inserted into FSB ALPHA to secure and hold open Route 9 to the south.

The most far-reaching battle for the ARVN came 25 February at FSB 31. The airborne troops had been under attack for days, but that afternoon they came under a three-pronged conventional assault by some 20 PT—T6 and T—54 tanks in conjunction with an estimated 2,000 infantry. Despite being greatly outgunned and outnumbered, the ARVN troops fought off two assaults with the help of tactical aircraft and artillery that destroyed several enemy tanks just inside the ARVN defenses. On a third attack FSB 31 was captured. Once again the Communists lost many more troops than the ARVN, plus 11 tanks on the assault, but the hill was in enemy hands. Based on intelligence estimates, it quickly became quite clear that the enemy had more artillery, tanks and combat troops than expected.

The airborne troops on FSB 31 were supposed to be rescued by an armored column moving north from Route 9, but the column never reached them in time. Between 25 February and 2 March this armored column and another fought the first head~to-head armor battles of the Vietnam War. The ARVN performed well in these battles and with the help of U.S. air strikes, decimated nearly 1,500 enemy troops and destroyed more than 20 tanks. The ARVN lost about 200 troops, three tanks and 25 armored personnel carriers. The airborne troops on FSB 30 held out until 3 March before abandoning the base. Enemy tanks assaulted FSB 30 but could not ascend the sharper slopes of the hill, so they stayed within range and provided direct fire support. Despite massive U.S. air power and artillery support that could be brought to bear in the areas north of F835 30 and 31, the enemy had created “no go” terrain for helicopters and most fixed wing airplanes. By sheer numbers in troops and firepower the enemy had the ability and audacity to move troops, tanks and vehicles in the open. Even with three divisions’ worth of air assets in the lOlst Airborne Division, all of the Air Force, Navy and Marine tactical aircraft, and dozens of B-52 strikes, the enemy had more firepower over most of the area of operation than could possibly be suppressed. Targets of opportunity were everywhere.

For nearly 3 weeks the armored column at A LUOI quite honestly “dragged its tracks.” It was clear with the deteriorating situation north of A LUOI, that the column could not advance toward Tchepone. Instead, it was directed to remain in a defensive role and an air assault was planned to reach the Tchepone objective.

On 2 March ARVN Marine units were airlifted to FSBs DELTA and HOTEL to relieve the lst Infantry‘s troops. On 3 March a battalion of lst Infantry troops was helicopter assaulted into LZ LOLO. This was one of the darkest days in Army Aviation history. Eleven UI-l Huey aircraft where shot down in the immediate area of the LZ that day, and some 35 UH-ls received combat damage. The air mission commander actually instructed the follow-on aircraft to, “Land to the burning aircraft!” that fateful day. Despite the losses, Army Aviation completed the mission to establish an FSB at the LOLO location. By 5 March the string of LZs and FSBs along the escarpment south of Route 9 and the Xepon River was complete. These included FSBs SOPHIA WEST and DELTA 1 along with LZs LOLO, LIZ and BROWN.

The FSBs and LZs along the escarpment provided the ground track for most helicopters to fly back and forth conducting resupply, combat assaults and aeromedical evacuation. These bases also provided the path for withdrawal after the assault on Tchepone. FSB SOPHIA WEST with its eight artillery pieces was also within range of the Tchepone area.

The 6th of March started as abeautiful, ciear blue day. B-52s changed that by pounding the Tchepone area that morning. That afternoon, two battalions of the ARVN lst Infantry Division were airlifted into L2 HOPE near Tchepone on the largest helicopter combat assault in the history of Army Aviation! An armada of 120 UH-ls departed Khe Sanh in a single—ship, 30-second separation formation on the 50+ mile round trip. A score of helicopter gunships and fixed wing, tactical aircraft flanked the UH-ls on that assault. Only one helicopter was shot down on an approach into LZ HOPE with a few others receiving “hits” from enemy fire.

On the ground, ARVN troops encountered little resistance and Tchepone was occupied for a few days. In the wake of the B-52s’ powerful strikes, ARVN troops counted hundreds of Norlih Vietnamese killed. A virtual “mountain” of food, supplies and weapons was also captured or destroyed. On 10 March units operating from LZ HOPE linked up to the south with units from SOPHIA WEST. This marked the end of Phases II and III and the beginning of Phase IV. Recall that Phase III was the exploitation phase during which search and destroy operations were conducted by units around their respective LZs and FSBs. Such operations were ongoing throughout Phase II.

Phase IV: The Withdrawal

Withdrawal from positions along the escarpment and on Route 9 was accomplished on foot and by helicopter extractions. From 11 to 14 March units from SOPHIA WEST and LIZ were extracted to SOPHIA EAST and DELTA I. By this time viturally all of the fixed locations of ARVN troops were in frequent contact with the Communists whose antiaircraft emplacements were everywhere, intent on defeating efforts to resupply or extract troops. The ARVN needed to execute an orderly withdrawal from a deep attack while under intense enemy pressure. (This is one of the most difficult military maneuvers to conduct.) At this point ARVN troops had little or no artillery support of their own. Many of their units were running dangerously low on ammunition, and the troops were very fatigued.

To complete extractions under enemy contact, most ARVN units had to move their locations at night. They had to break contact with the enemy and then find a suitable pickup zone (PZ) where extractions were feasible. Frequently, extractions could only be completed after or during intense artillery, helicopter gunship and tactical air support. By 18 March ARVN units, with mounting losses, had withdrawn east on the escarpment south of A LUOI.

On 19 and 20 March evacuation of armor and airborne units commenced with the closing of A LUOI. The armored columns moved east along Route 9 without too much difficulty until reaching FSB BRAVO where they ran into a Communist blockade, ambushes and tanks.

From 20 through 22 March the last armored columns on Route 9 tried to return to Khe Sanh, but most were ambushed and destroyed. This marked the end of the Route 9 withdrawal except for stragglers who managed to come through during the next day or so.

On the escarpment, all ARVN lst Infantry Division troops were extracted by 2] March, but not be fore Army Aviation became engaged in intense combat the day before. While making repeated flights to extract ARVN troops from PZ BROWN, 10 UH-IH helicopters were shot clown. About 50 more received combat damage. Once again Army Aviailon was put to the ultimate test. It took serious losses, but completed its mission!

The ARVN Marines were the last units left on the escarpment at FSBs DELTA and H0TEL. On 20 and 21 March a brigade on FSB DELTA came under continuous attack. Four times combined human wave and tank attacks were repulsed with the aid of U.S. artillery and air support to include close-in B-52 strikes. North Vietnamese tanks and high troop concentrations appeared everywhere along Route 9 and on the escarpment.

On 22 March the ARVN Marines were finally driven off of FSB DELTA by flame–throwing tanks. The next day as many Marine units as possible were extracted from Laos and on 24 March the last elements of ARVN troops were extracted from FSB HOTEL. LAMSON 719 ended with a tremendous show of North Vietnamese firepower, stopping short of advancing into South Vietnam toward Khe Sanh to continue the battle. LAMSON 719 fighting continued up to 6 April, but after 24 March only a couple of 1-day raids were conducted into BASE AREA 611 with little casualties or consequence.

Battle Facts and Statistics

Throughout LAMSON 719, Army Aviation units continued to encounter intense enemy antiaircraft fire while resuppliying troops and extracting the wounded and dead. Most approaches to LZs along the escarpment and on Route 9 received heavy fire oing in. In the LZs, the aircraft re eived mortar and small arms fire as well as occasional artillery barrages. But the worst part of the gauntlet came when the UH-l Hueys would depart the LZs and attempt to climbout. Then a droning fusilade of fire would be unleashed from several locations, making it difficult to maneuver away from the fire.

The most frequently used and frightening antiaircraft weapons the Hueys encountered were the 12.7 mm or 50 caliber machine guns. These weapons had a distinctive sound and fired tracers every few rounds, which looked like hasketballs or pumpkins coming at the aircraft. Even with two and four gunships for support and occasional tactical fighters, some sorties could not be completed. Toward the end of the operation, the North Vietnamese altered their strategy by letting some aircraft make approaches without being shot at, then suddenly unleashing mortar, artillery and antiaircraft barrages at the helicoptrs upon landing and taking off. At times more than 20 ARVN soldiers would be lifted out by straining UH-1s, with soldiers clinging to the skids. Media port ayals of these incidents were used as proof the South Vietnamese had been “routed” from Laos.

Weather was a serious problem, hindering LAMSON 719 operations. Most aircraft were stationed on the oast more than a half-hour flight to Khe Sanh in a UH1. Refueling and staging was done mainly at Khe Sanh or FSB VANDERGRIFT. Bad weather over Laos, Khe Sanh or the coast too often caused delays or cancellation of missions, occasionally at critical moments during the battle.

Results of the LAMSON 719 operation brought criticism from some about the concepts of airmobility and fire support bases. ARVN troops were unable to effectively patrol around their FSBs and thereby failed to prevent enemy hugging tactics. Successful patrol was necessary to provide security for helicopter operations. Also, fixed positions engaging superior enemy firepower were questionable and provided a distinct disadvantage in counterbattery fire – a common occurrence during LAMSON 719. The Communists had greater mobility, familiarity with the area, and longer artillery standoff ranges than the ARVN. Hence, greater mobility in the deep attack probably would have been more serviceable. While the concept of airmobility may have been questioned, a review of the battle statistics shows that Arrny Aviation could perform its mission in a midintensity conflict, which includes heavy concentration of antiaircraft fire (figures 4 and 5). In such an environment, a significant loss of aircraft and people was inevitable! However, considering the number of sorties, the loss rate was remarkably low.

The outcome of LAMSON 719 on the ground was questionable. But the successful performance of Army Aviation supporting a deep attack as a maneuver element of a combined arms team (which included an allied force) proved the concept of airmobility without doubt. The North Vietnamese knew well the four employment principles of air defense: mix, mass, mobility, and integration. But, Army Aviation countered enemy efforts more times than not.

The significance and success of the helicopter on the mid-intensity, mobile battlefield finally proved the helicopter’s unique capabilities that had until then only been anticipated/conceptualized, never before proven in combat. An attack of such magnitude never could have been accomplished from start to finish in just 45 days without the airmobility capabilities of the helicopter. Without U.S. firepower and airmobility tactics, a deep attack into the Communist’s most-defended base areas (which incorporated intense enemy firepower and large troop concentrations) would have been foolhardy. The result would be little success and probable casualty rates in excess of the near 45 percent level experienced by the ARVN task force.

LAMSON 719 was different from overall operations in South Vietnam, and also different from current tactical doctrine in Army Aviation. Throughout South Vietnam, helicopters generally operated in a low-intensity antiaircraft fire environment. Helicopters usually were only sporadically engaged, primarily with just small arms fire. During combat assaults, gunship support was often successful in suppressing enemy fire.

Even up to the standdowns in 1972, low level (nap-of-the-earth) flying was prohibited and viewed as unsafe. Aircraft were supposed to fly at 1,500 feet above ground level in Vietnam and at least 3,000 feet above ground level in Laos and Cambodia.

On single helicopter missions, tight circling approaches and climbouts were typical for getting into and out of LZs. Multiship combat assaults also conformed to the altitude restrictions and usually were conducted in lifts of UH-ls in tight formations to get as many aircraft as possible into a PZ/LZ. Usually one gunship team of two helicopters would provifle fire support around a PZ/LZ flying a racetrack pattern on one side of the flight at an altitude 500 to 1,000 feet above ground level.

in Vietnam such tactics were successful, but in Lao they were disastrous. Before the end of LAMSON 719 single helicopter sorties were routinely flown at low level; combat assaults were conducted by single ship landings with 30-second separations, and gunships made runs from higher altitudes. The LAMSON 719 battle did more than any other operation in the history of the Vietnam War to revert Army Aviation doctrine to the development of nap-of—the-earth flight tactics (such as were being developed at the Aviation Center, Ft. Rucker, AL, in the late 1950s and early 1960s). Also Vietnam helicopter tactics were moved away from close formation combat assaults!

Who really won the LAMSON 719 battle? Both sides claimed victory, but a review of the major objectives of the operation showed that it was more of a success for the South Vietnamese. They did interdict into Laos and disrupt the flow of enemy troops and supplies along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. In fact, because of this campaign, it was more than 1 year before North Vietnam launched any significant offensives in the south.

LAMSON 719 revealed some serious flaws, particularly in the Vietnamization effort. The ARVN force was not sufficient in size, and it was a long way from being able to provide its own air and firepower to thwart the determined Communist aggression.

Despite the Communist losses, the significant losses sustained by ARVN troops damaged the morale and confidence of the South Vietnamese. In particular, the Vietnamese people were shocked and hurt that so many dead and wounded were never extracted from the battlefield. Recall that the Vietnamese culture was dominated by ancestor worship: Failure to return the bodies of fallen soldiers accentuated the grief of family members.

LAMSON 719 was supposed to last up to 90 days instead of only 45 days. Clearly, the Communist’s significant counterattacks shortened the duration of the operation. Finally, within a week after the battle, Communist activity on the Ho Chi Minh Trail had resumed with its usual earnest, never to be seriously threatened again.

| Killed in action |

Wounded in action |

Missing in action |

Equipment Lost (excluding aircraft) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. | 102 | 215 | 53 | (none in Laos) |

| RVN | 1,146 | 4,236 | 246 | 71 tanks |

| 45% casualty rate for committed troops in Laos. | 96 artillery | |||

| 278 trucks | ||||

| NVA | 14,000 | Unknown | Unknown | 100 tanks |

| Estimated 50% casualty rate. | 290 trucks | |||

| Figure 1: Casualty Statistics | ||||

| Aircraft | Total Aircraft |

Aircraft Damaged |

Damage Incidents |

Aircraft Lost |

Percentage Lost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OH-6A | 59 | 22 | 34 | 6 | 10 |

| UH-1C | 60 | 48 | 66 | 12 | 20 |

| UH-1H | 312 | 237 | 344 | 49 | 16 |

| AH-1G | 117 | 101 | 152 | 18 | 15 |

| CH-47 | 80 | 30 | 33 | 3 | 4 |

| CH-53 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 2 | 13 |

| CH-54 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| OH-58 | 5 | No Data | No Data | No Data | No Data |

| TOTAL | 659 | 453 | 644 | 90 | 14 |

| Figure 2: Helicopter damage and Loss Statistics | |||||

The final battle tallies and aviation statistics were taken from the lOlst Airborne Division (Airmobile) afteraction report (April to May 1971). The afteraction report was declassified after 12 years {Department of Defense Directive 5200.10). The casualty numbers shown in figure 4 are based on the total troops committed in LAMSON 719. Official dates given for aviation statistics were 8 February to 24 March 1971. or 45 days. Damage and loss statistics for the Army Aviation rotary wing assets committed to the operation are shown in figure 5.

Next month LAMSON 719 coverage concludes with “Part III: Reflections and Values.” In it, the lessons learned from LAMSON 719 will be summarized.

This article is Part 2 from a three part series that was written by our own Rattler 20, Captain Jim E. Fulbrook, Ph.D., MSG and published in the United States Army Aviation Digest in June, July and August of 1986.

Webmaster note: This article refers to the operation as “LAMSON 719”. The correct name of the operation is actually LAM SON 719, referring to the birthplace of a Vietnamese hero who led an army to expel the Chinese from Vietnam in the 15th Century. The use of “719“ signifies the year “1971“ and the battle area along Route 9. Also noteworthy is the fact that the scan of the articles was less than optimal, several of the images in the article were unusable. You can see the original scanned documents here.